A radio announcement that will be familiar to many

“Attention! There is a wrong-way driver headed your way on freeway XXX between junction YYY and ZZZ. Stay in the slow lane and out of the passing lane...”

The first German radio station to feature public announcements of wrong-way drivers was the Bavarian broadcasting station (Bayerischer Rundfunk) which is why the problem was initially seen as “purely Bavarian.” We now know, however, that wrong-way driving can occur on all roads with two or more lanes for one direction of travel, except where access is regulated by toll stations (e.g. in Italy and France). Research into the causes of wrong-way driving began in 1980. Interviews, reconstructions and on-site analyses have shown that there is no one single cause of wrong-way driving on freeways or other controlled-access roads.

First of all, we have to distinguish between “intentional” and “unintentional” wrong-way driving.

Wrong-Way Driving

Intentional wrong-way driving happens, for instance, if someone has missed their exit and then reverses on the hard shoulder or if a driver turns around in a traffic jam to drive back to the last exit on the hard shoulder. Such actions are strictly illegal but cannot be prevented through structural or road design measures.

Unintentional Wong-Way Driving

There are several causes of unintentional wrong-way driving:

- poor road layout and signage,

- lack of visibility,

- disoriented drivers,

- distracted drivers.

Poor Road Layout and Signage

Fog and darkness, especially in combination with poor road layout, can result in unintentional wrong-way driving. Signs that are difficult to read or display too much information may disorient and confuse drivers. Several of the incidents of wrong-way driving that we analyzed involved drivers who had gotten lost in complex freeway interchanges for some time. They ended up so disoriented that they drove in the wrong direction. Freeway truck stops and service stations are also problematic. Since people can move about freely in these areas, there is also a chance that they may re-enter the freeway in the wrong direction.

As we know from research into human error, several issues usually combine to result in a mistake being made, such as time pressure and distraction. The same is true when it comes to wrong-way driving (i.e. orientation problems and distraction).

One of the most common questions is: Why do wrong-way drivers fail to notice their mistake for so long and keep driving in the wrong direction for several miles? Research clearly shows that most drivers quickly notice their mistake. They suddenly find themselves in extraordinarily stressful circumstances, however, leaving them unable to think of a rational solution. One driver, for example, when asked why he drove in the wrong direction for such a long time, replied: “I was looking for a good spot to turn around.” We all know that there is no such spot on a freeway.

Solutions

One suggested solution are spike strips, which are deployed when a vehicle drives the wrong way up a freeway exit ramp, for example. While this approach may seem like a good idea, it does not take into account that there are 226 such ramps and interchanges in Bavaria alone. Not only would implementing this solution require extensive roadwork, it would also have to be ensured that police and ambulance vehicles can safely disarm the system in order to be able access the freeway against the direction of traffic in an emergency.

More suitable solutions include:

- clear signage to reduce the chances of drivers getting lost or disoriented,

- clearly marked entry and exit ramps with conspicuous signage:

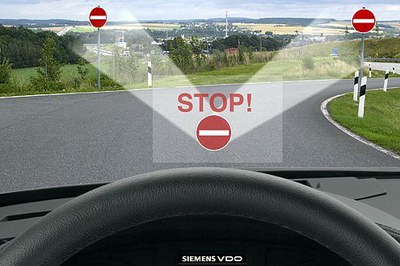

- integration of warnings into navigation systems to prevent wrong-way driving:

- Integration of wrong-way driver warnings into navigation systems:

Literature